Two linemen haunt me.

One is Jack Trice, a tall broad man with a soft smile who became Iowa State University’s first Black athlete in 1922. He suffered fatal injuries in his first major football game against Minnesota in 1923 and died two days later leaving behind a young widow and an enormous legacy.

The other is Grandpa, a towering influential figure in my life who traded in decades of hard work on power lines in a small Illinois town for the lapping waves of a nearby river house. During summers of boating, he enthralled us with rollicking stories of youthful adventures and crucial life lessons. He died abruptly a few years ago after being diagnosed mere months earlier with aggressive cancer that had spread everywhere.

Grandpa’s death led me into the mystery of Jack Trice’s missing jersey number. Along the way, my wife and I formed a company named Kagavi, held together by the legacy of two linemen. Jack is Grandpa. Grandpa is Jack. This is their story.

_____________

PART ONE

I’ve always been drawn to Jack’s story as an underdog, because I am one. I was born deaf and grew up in Ames, Iowa in the shadow of Iowa State University. From an early age, I was very aware of being different–my first hearing aids were so big I had to wear them on my chest. There was no hiding from my challenges, but the lack of sound didn’t bother me too much. I already had it figured out. One night as my mother tucked me in bed, I happily told her I would be able to hear like my older brother when I grew up.

To battle my deafness, I ravenously consumed all available pieces of knowledge. I spent many happy hours hidden in the long rows of the public library. Here was one way I could live my life without needing help. The written word became my constant companion. In my bedroom, surrounded by teetering stacks of books, I reached into my art case to create my own stories as the world outside pushed me away. I inhaled my fruit-scented color markers so often, my nostrils were stippled with the rainbow.

The playground offered me another way to communicate without words. Sports had their own defined rules and every recess period, a gaggle of us often played football on the grass fields. My friends shouted their favorite heroes: John Elway, Bo Jackson, Joe Montana. I always wanted to be Jerry Rice. So it went. We drew up plays in the soil and used secret signals. Then it would come: the visceral thrill of the nod. The stop and go play. The long one. Sprinting down the field as the long spiral fell towards me, I felt normal.

Inevitably, I was drawn to crisp fall afternoons watching the Cyclone football team vainly battle against superior foes. The warm air of Hilton Coliseum cut through bitter winter gales as we watched Johnny Orr’s high scoring basketball teams. Through these ISU sports experiences, I learned about a Black football player named Jack Trice who died in his first big game for the Cyclone football team. I held Jack’s gaze and felt a kinship with him. He knew what it was like to be different. Who was Jack?

_____________

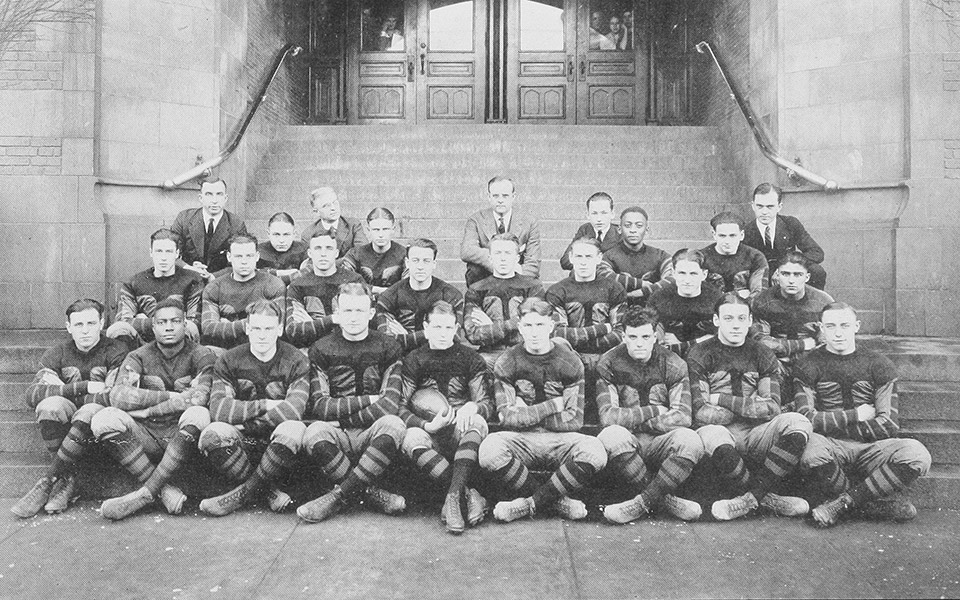

The few pictures of Jack Trice that survive show a strapping young man with a ready smile. Jack had a broad frame and explosive strength that served him well in various sports. The classroom offered Jack a chance to work towards his avowed goal of helping Black farmers in the south and Jack excelled there as well. Friends recalled his gentle personality and deferential nature.

John “Jack” Trice was born in 1902 as the only child of Green and Anna Trice—both children of slaves. Jack grew up in the small Ohio town of Hiram, which benefited from the progressive influence of nearby Cleveland–just 40 miles northwest. In 1909, Jack’s father Green died from kidney disease and left Anna to raise Jack alone. In the fall of 1917, Anna sent him to Cleveland to live with his Uncle Lee and Aunt Pearl and attend East Technical High School. Anna felt Jack would benefit from being “among people of his kind to meet the problems that a Negro boy would have to face.”

In short order, Jack became one of the best athletes at East Tech and departed in 1922 as the school record holder in the shot put. The June Bug yearbook said, “John Trice is undoubtedly the best tackle that ever played on a Brown and Gold football team.” An impressive accolade considering the strength of the East Tech football teams that often ran roughshod over opponents.

As a junior, Jack’s team traveled to Washington by train to face off against an Everett team in the national high school championship game at their stadium. East Tech lost 16 – 7 in a close game marred by multiple fumbles, but Coach Sam Willaman highlighted Jack as one of the defensive stars of the game. In Jack’s senior year, the East Tech team went undefeated, outscoring their eight opponents by a cumulative score of 320 to 28—an average of 40 to 3.5. Eager to test his squad against the nation’s best, Coach Willaman tried in vain to find another postseason opponent but could not.

When Jack graduated from East Tech in early 1922, his plans were ambiguous enough that he worked as a watchman and made plans to attend a local school. He spent time with his longtime girlfriend Cora Mae Starland and their romance culminated in an elopement in late July. Meanwhile, Coach Willaman parlayed his incredible East Tech football success into a new job as the head football coach at Iowa State College. Naturally, Coach Willaman convinced multiple East Tech players to follow him to ISC including Johnny and Norton Behm, Champ Hardy, and Jack. For Jack, this meant leaving behind his new bride in Ohio, but the opportunity was too good to pass up. Not every school was interested in Black football players.

When Jack arrived in Ames, Iowa in 1922, he became the very first Black athlete for Iowa State College. Ames was a sleepy town in the middle of Iowa and housing on campus was segregated, forcing Jack to find housing in downtown Ames. Throughout Iowa, the Ku Klux Klan enjoyed record popularity, but they were still staying mostly out of Ames. Jack supported his college education with two jobs–a custodial position downtown and a job with the ISC athletic department in State Gym. In fall 1922, Jack turned in a strong performance on the freshman football squad. Many felt he would be a future star for the Cyclones. The Iowa State Student newspaper was quick to praise Jack as “a mountain in the line, being in every play, no matter whether it was a pass, plunger, end run, or punt. He was generally the first man to get there.” On the gridiron, the varsity team struggled to a 2 – 6 record with the final game an ugly 54 – 6 loss at Nebraska. In the spring of 1923, Jack joined the track team and captured the freshman Missouri Valley Conference shot put title with a new school record throw of 41’8” and also placed fourth in discus.

After a brief summer in Ohio, Jack returned to Ames with his young wife Cora Mae. Big things were in store for the 1923 football season.

_____________

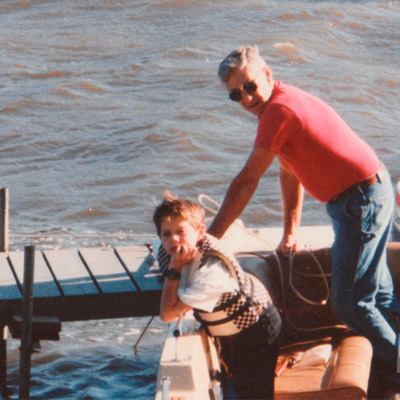

During my childhood, every year we counted down the days to summer vacation and Grandma and Grandpa’s river house. They lived just four hours away across the Mississippi River and at the mere mention of the river house, my brothers and I raced to the library to load our groaning backpacks full of Hardy Boys and Uncle Scrooge books. We knew at the end of our car ride would be Grandma with a plateful of homemade cookies and Grandpa grinning away, his head full of thrilling stories.

Located outside of town, the river house was modest—just one bedroom with comfortable chairs and things scattered about, but we regularly fit six or seven people in there. The boat bobbed on the water nearby and Grandpa could be found constantly working in it. Grandpa had large hands rugged by decades of linemen work and even his fingertips were squared off. He had high cheekbones and a natural tan which spoke to a mysterious heritage, full of speculation. When working on a project, Grandpa had a habit of moving his mouth just so. It looked as if he was lightly chewing invisible gum. Any project he was working on was an excuse for me to tag along and observe. I studied his face and imitated his movements. With Grandpa, I didn’t have to worry about being deaf. I could just watch and learn.

My two brothers and I darted around the yard with sparklers and water guns. Treasure maps were created and lazy afternoons were spent fishing. We learned how to water ski and tube on the river. Grandpa’s dog-eared issues of Nintendo Power were consulted to complete digital triumphs. Evenings under the glimmering Milky Way were full of grilled food on smoky campfires and Grandpa’s thrilling stories of his own adventures. Through his words, we tiptoed through haunted houses, dodged angry rattlesnakes in the frontier, raced stock cars in the dusty Midwest, and went cave spelunking through the Ozarks.

Every container, every cabinet, and every drawer held the promise of even more stories. Here was the pile of bowie knives. Holding the cool steel, I could taste the salt of the jungle. Carved duck decoys bobbed before my eyes. Pungent fishing lures coated my taste buds. And in the corner, Indian trade blankets full of giddy patterns teased cool nights in the desert. I couldn’t hear Grandpa’s voice telling the stories, but I could certainly see and feel them. I hated going to bed, because there was always a chance it was just a dream. When I woke up, I kept my eyes squeezed as I inhaled the air and felt around with my hand to confirm that I was indeed at the river house.

Eventually, the winters became too much and the river house was sold. Grandma and Grandpa gutted a home near the beach in Florida and rebuilt it. Long summers at the river were replaced by short holidays at the beach. We spent many happy winters there. It seemed Grandpa’s stories would never end.

_____________

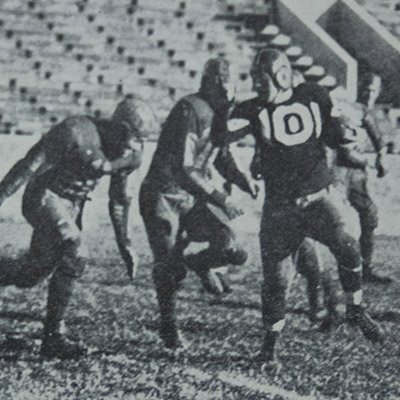

During the 1923 season, the Iowa State College football team, often referred to as Ames, played eight opponents. Football games of this era were a mixture of exhibition-level minor games and major college games, which were usually conference games. Additionally, due to rules in effect, players played both ways on offense and defense. Jack’s right tackle position meant he anchored the right side of the offensive line and on defense he played a position equivalent to defensive end.

The Cyclones faced off against nearby Simpson College for the first game of the 1923 season on September 29. The Cyclones eleven beat Simpson by a 14 – 7 score in a muddy game at State Field in Ames. As Cora Mae watched, Jack excelled with a blocked kick, forced fumble, and recovered fumble. Little did Jack know this was his first and last home game. (Note: the picture below is from a home game several years earlier.)

Next up was powerful Minnesota and the Ames team travelled to Minneapolis by train for the game on October 6. Minnesota’s stadium seated 27,000 and dwarfed State Field which only held under 6,000 at the time. On a pleasant mid 60 degree day, the “tough Ames eleven” gave Minnesota all they could handle in a 20 – 17 loss. In the first half, Jack suffered a broken collarbone, but stayed in to battle before suffering a second severe injury in the third quarter. Cora Mae kept track of the game via a Grid-Graph in State Gym along with many other Cyclone fans and knew when Jack was hurt.

Captain Ira Young and Harry Schmidt gingerly helped Jack off the field as the Minnesota crowd reportedly chanted “We’re sorry Ames.” On the sidelines, Ames trainer Dr. Benjamin Dvorak ignored Jack’s protests and took him to the nearby campus hospital to consult with other doctors including the Minnesota Athletic Director. After debating Jack’s injuries, it was deemed safe for Jack to ride the overnight train back to Ames with the rest of his team.

On Sunday afternoon, Jack’s condition worsened and that night a stomach specialist from Des Moines was summoned. Upon arrival, Dr. Oliver Fay felt surgery would kill Jack, so they could only wait. Monday afternoon, Cora Mae came to Jack’s room again where they met eyes for the last time. With one last breath, Jack was gone.

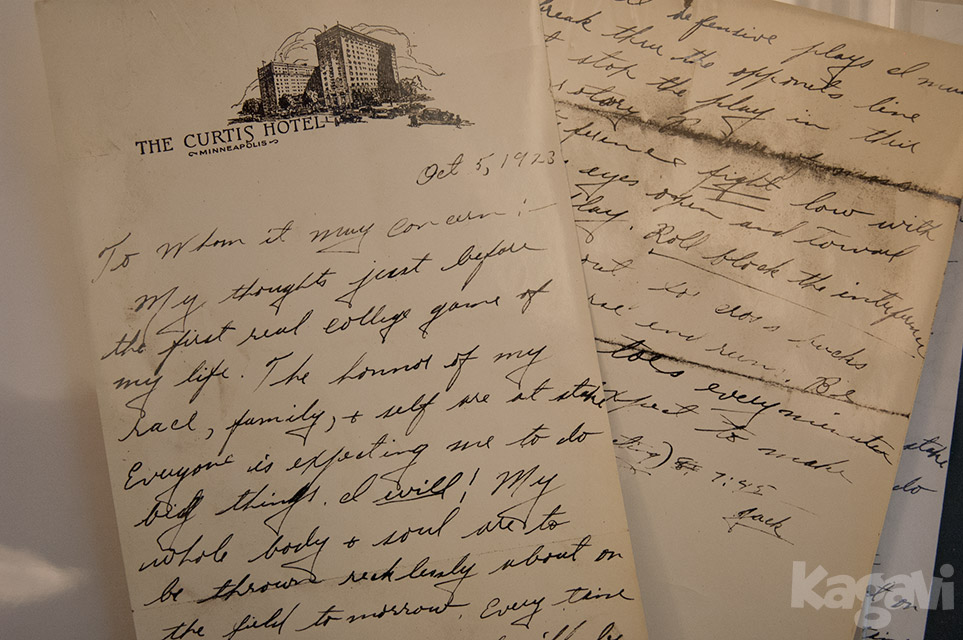

The Iowa State College campus shut down for the funeral on Tuesday where Jack’s casket was draped with a cardinal and gold Ames blanket. During the service, Iowa State President Raymond Pearson read a letter that had been discovered in Jack’s coat pocket with permission from Cora Mae.

Written by Jack the night before the Minnesota game, it read in part:

“My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family, & self are at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body & soul are to be thrown recklessly about on the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped, I will be trying to do more than my part. On all defensive plays I must break thru the opponents line at [sic] stop the play in their territory. Beware of mass interference & fight low with your eyes open and toward the play. Roll block the interference. Watch out for cross bucks and reverse end runs. Be on your toes every minute if you expect to make good. Jack.”

The ISC community raised several thousands of dollars for Cora Mae and Jack’s mother Anna and created a plaque to honor Jack’s sacrifice. The plaque hung in a forgotten corner of State Gym as Jack’s story drifted from memory.

_____________

PART TWO

One weekend in November a few years ago, as light snow flurries turned to rain, my wife and I sat in a pizza place eating dinner. The phone rang. It was Grandma. My wife answered and her face changed. I stopped eating. They had been to the doctor’s office and Grandpa had stage four cancer that had spread all over the place. We had no idea.

The following month, our annual Christmas trip to Grandma and Grandpa’s house was somber. The cancer and emphysema made it hard for Grandpa to breathe. The stories dwindled. Grandpa couldn’t leave the house, so we talked about days on the river.

One cold February morning, I was at work and saw my wife walk in. I knew.

_____________

The morning after Grandpa’s death, he walked into our sunny bedroom, sat on my side and looked at me with a bemused expression before simply saying, “Hey buddy.” The dreams have not stopped since. In most of them, I’m back at the river house, but the surroundings are different. No Grandpa. Many of them end with Grandpa entering the room and saying, “I’m back” before the dream abruptly cuts off.

Later that same week, I found myself overwhelmed with feelings of guilt and confusion at how quickly he was gone. I didn’t have a chance to pursue any of my dreams while Grandpa was still alive. I felt like a failure. During the weekend, without work to distract me, I collapsed in the hallway, overwhelmed by tears for the first time. My wife held me and we cried until the sun went down.

As the absence of Grandpa became more real, I found myself missing the stories. Any time we got together, there was always a story. Grandpa wasn’t really someone who got older, rather he just became more weathered. Even in his last years after moving to a retirement community with Grandma, he still kept an enormous knife under his car seat. Always a story to be had. The dreams continued unabated, teasing me with a hint of his presence. I became worried I would forget everything.

Less than a year after his death, my wife and I moved from New York to California. While driving across the country, we took a detour to the river house. I hadn’t been back for well over a decade, but felt drawn to it once more. I knew it didn’t exist anymore, but it was still jarring to see the barren concrete slab overlooking the murky waters. The memories swept away, just like Grandpa. When we left, my mood matched the gray sky.

We settled in a small beach town south of Los Angeles and my wife got a speech therapist job with her newly minted master’s degree. I kept working in management, adrift with my talents withering away. Driven by shame, guilt, anger, and many more emotions, I quit my job one day with no real plan. The end of Grandpa’s life was the beginning of bringing Jack back to life.

_____________

I wanted to be a storyteller just like Grandpa and that day was now. Suddenly paralyzed by an empty calendar, I locked myself in our home and drove my wife and myself mad for months while considering hundreds of company names and the meaning behind them. Only when I had a solid concept would I be able to move forward. One day after yet another dream with Grandpa, I made the blindly obvious leap that the company name should mean Grandpa’s Stories. Renewed, I searched for just the right combination of words that would mean just that. My wife and I often laid awake in bed at night as I read off a long list of proposed company names. We finally settled upon a combination of words that meant “chronicles” and “grandfather.” It just felt right. Kagavi was born.

With that settled, the stories started to flow. For several months, when my wife got home from work, we brainstormed ideas together and I showed her designs that I had created during the day. I wanted our products to be limited edition and tell a story. I thought about Grandpa constantly. Could he see me now? I thought of the objects in the river house. The bowie knifes and fishing lures. I remembered sleeping under the Indian trade blankets. The strong geometric patterns stood as a visual representation of the river house. Those blankets nurtured a strong love of bold textile design, because they became inextricably linked to Grandpa’s adventures.

We started work on original story concepts, but after a few months it became apparent that our short-term focus should be on ISU stories. I grew up in Ames and had so many Cyclone friends who would enjoy seeing projects based on ISU. I started researching ISU sports history in order to create vintage designs with meaning. I felt drawn towards the untold fables of ancient Cyclone history. As a college student, I occasionally stopped by the special collections room on the top floor of Parks Library to pore through piles of dusty documents. I learned about the Nunawading Giant, the Roland Rocket, and the thrilling runs of the Eel. So many stories that had faded from memory.

As I leafed through ISU sport history, I kept going back to Jack. I recalled how playing sports made me feel normal and my childhood interest in Iowa State’s first Black football player. We were both different. Now with Kagavi, I had the chance to study Jack’s story more. I wanted to know more about him, but in order to understand his life and legacy, I needed to first understand the role of college football in American society.

_____________

As America struggled to recover from the Civil War, the first official college football game took place between Rutgers and Princeton on November 6, 1869. The 1880s and 1890s saw many universities start “foot-ball elevens” on campus. Football gained a reputation as a brutal sport with multiple players killed every season, yet the crowds kept coming. College football started to approach the popularity of professional baseball in America. The dangerous tactics continued and in 1904, the Chicago Tribune reported there were 18 deaths that season. Amidst cries for reform the following year, President Teddy Roosevelt, who had a son on the Harvard freshman football team, used his influence to push for change.

In the waning embers of 1905, representatives of 68 teams ensconced at the luxurious Murray Hill Hotel near Grand Central Station in New York. After a meeting on December 28 that raged for nearly nine hours, a new rules committee was established for intercollegiate football. The old rules committee was asked to cooperate in reforming the game and making it safer, but the new committee threatened to move forward with or without them. A few weeks later in early January, Harvard proposed new rules such as the creation of the forward pass and the neutral zone among other safety changes. After a few more months of wrangling, the new rules were formally accepted and the era of modern football began. Quarterbacks, halfbacks, and fullbacks all became threats to throw the ball at any time. The game became more open and free-flowing. Further rule changes enacted in subsequent years only solidified the transition away from a rugby-style game.

Another mark of the overall maturation of the game was the evolution of uniforms. In the nascent days, uniforms were wildly inconsistent from team to team and sometimes players all wore different outfits. Quilted pants and vests were common. Uniforms eventually started to utilize a wool sweater with all players wearing the same color and many teams opted for a simple letter on the chest. School colors weren’t strictly adhered to. Players used wool blankets on the sidelines to stay warm.

In 1908, Washington & Jefferson reportedly became the first school to add numbers on the back of jerseys, but it wasn’t until 1915 that most schools had adopted the change. For a brief two decade transitional period between woven letter sweaters to fully numbered jerseys, (which were standardized in 1937), a distinctive period of jersey design emerged. Friction strips and patches started to appear on the front of jerseys. Some teams even used them as logos while other teams experimented with geometric designs. Below is a 1928 game between Iowa State and Oklahoma which shows both types of designs.

The familiar vertical friction strips on the front of jerseys are still commonly used to illustrate the “leather helmet” era in popular culture. It was during this period that Jack Trice arrived at Iowa State College.

_____________

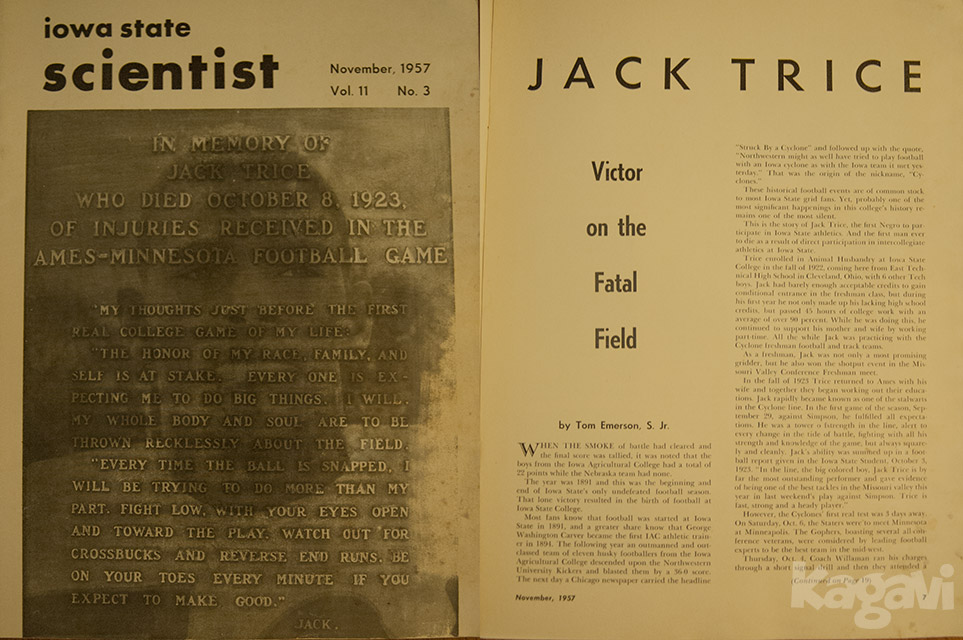

Many people have conducted great research into Jack’s life, but it started with a young Iowa State University journalism student named Tom Emmerson who wrote about his tale in 1957. (The plaque on the cover of the magazine was made in 1923 to commemorate his death, but has been missing for decades. The reflection of a Black person was for artistic purposes and doesn’t exist on the actual plaque.)

In the early 1970s, partially sparked by the counter-culture movement, momentum built towards naming the new football stadium under construction after Jack. A consensus couldn’t be reached and the stadium opened as Cyclone Stadium in 1975. Remarkably, the community kept momentum building towards recognizing Jack and in 1984, the field was named Jack Trice Field at Cyclone Stadium. Finally in 1997, the entire stadium was renamed Jack Trice Stadium.

As I sifted through documents, I kept looking for Jack’s jersey number, but it was nowhere to be seen. I approached the university and the athletic department, but was told by everyone that Jack’s number had been lost to history—if he ever had one to begin with. If there’s one thing I can’t resist, it’s a good mystery. Surely it was out there somewhere. My childhood interest became a full-blown obsession. How could Jack’s number have slipped through the cracks? Numbers are the lyrical language of sports.

Jack’s mystery led me into the stories of his teammates and those who followed in the 1920s. Who were they? Where did they end up? Years of the familiar jerseys with five stripes. I started recognizing Jack’s teammates in game photos and called them by their nicknames. Fat. Mope. Spike. I gazed entirely too long at sepia tinted images of State Field and found myself walking along the field with the strong arched windows of State Gym in the distance. Just a whisper in time. Jack was just the beginning. There were the Behm brothers. Holloway Smith, ISU’s second Black football player a few years after Jack, cast a compelling shadow. The piercing stare of Walt Weiss stayed with me. All of these stories scattered to the winds.

I retraced the well-trod path of previous researchers looking for just one sheet or box that had been overlooked. When I was told no, I asked again and again. At night, I dreamed of Grandpa’s smile. During the day, I saw Jack and his teammates. Jack and Grandpa became one, haunting me at all times. I felt as if I was cheating death for them–I would bring them back to life. The obsession didn’t stop with Jack’s jersey number. Spurred by pictures of football players huddled under wool blankets, my zeal spilled over to the Indian trade blankets of the river house.

_____________

Wool blankets have been traded for hundreds of years throughout the world. American Indian tribes valued the versatility of wool fabric and often traded animal pelts for factory made blankets. Hudson’s Bay Company was one of the first manufacturers to wade into this new market. Their iconic white point blankets with red, green, yellow, and blue stripes were originally created in 1780 and can still be bought today in the same style. A few tribes created their own blankets, most famously in the American Southwest. The Pueblo influenced other tribes including the Navajo, Zuni, and Hopi. (Below are two of my favorite Navajo chief’s blankets from past episodes of Antiques Roadshow.)

Navajo weavings were inspired by other cultures and used Spanish wool and Mexican dyes. After the Indian Wars, trading posts were established and the Navajo started weaving rugs instead of blankets out of economic necessity. An opportunity arose for factory blankets to fill the gap.

Barry Friedman, who might be even more of a certified lunatic than I am, wrote a wonderful book called Chasing Rainbows, which exhaustively detailed the history of Indian trade blankets and camp blankets in America. Friedman discovered the first instance of an Indian trade blanket in a 1892 ledger entry for the J. Capps mill in Jacksonville, Illinois. From there, Indian trade blankets were manufactured by a few different companies through the late 1920s. The Pendleton Woolen Mills company created their first Indian trade blanket in October 1896. The Great Depression bankrupted many and World War II finished off all except Pendleton.

Pendleton’s early success with blanket designs can be attributed to one influential designer: Joseph Rawnsley. He was the primary Pendleton designer and often travelled through the southwest working with local tribes to see what designs they preferred. Continuing the long history of blending different cultures into blanket designs, Pendleton blankets are accurately described as designs made to sell to tribes using their own cultural inspirations. Rawnsley died in 1929 after a troubled life, but many of his famous designs are still manufactured today. Despite being woven quicker on a machine, Pendleton blanket designs could still take up to a year to create. Pendleton blankets were quickly accepted by many tribes and remain an important part of ceremonies to this day.

Pendleton’s role in college football history is not as well known. During this imaginative era of textile design, Pendleton started creating athletic achievement blankets. Many schools ordered lettered blankets for athletes. A special blanket was created for the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles. All-American football players began to be awarded Pendleton blankets. The Pendleton archives supplied me with some historical pictures. Here we can see some of the 1941 All-American players with their blankets woven by Pendleton.

_____________

With these influences swirling around in my mind, one day they came together as if they had always been so. Driven by my desire to discover Jack Trice’s jersey number, I had learned about the jersey history of the Cyclones football teams of the 1920s. The 1921 teams started using the vertical five stripe design and when Jack arrived in 1922, the team changed the stripe design slightly. In later years, the jerseys had six stripes.

So many Cyclones teams with the striking vertical stripes. My favorite blankets were nothing but stripes and diamonds. Grandpa’s blankets. The jerseys stripes came to a point. American Indians and football; both uniquely American. They melted together. Grandpa’s spirit flowed through my pen. I filled page after page with blanket designs. The dreams took form in long arching lines, repeating diamonds, and strong stripes. Over and over, I drew striped variations. My grief was palpable. My pen dug into the pages. This was how I could bring Grandpa back.

After getting the necessary approvals from Iowa State, I contacted Pendleton and started the long process of creating a Kagavi x Pendleton vintage ISU stadium blanket inspired by those Cyclone football teams and Grandpa’s Indian trade blankets.

_____________

Just a month after Pendleton started weaving our blanket, Jack’s jersey number was found in a game program inside a nondescript box at Simpson College. Somehow for so long, his jersey number had been overlooked in the archives of a college less than 100 miles away. It was a step that seemed absurdly easy given the months of research I had done. The game program was from the Simpson versus Ames game on September 29, 1923, which was Jack’s first varsity game. A simple turn of the page revealed the mystery number as 37. After my shock receded, I wrote a story about the discovery here.

_____________

When the Pendleton sample blanket arrived a few months ago, I pried open the tightly taped box and saw the sample blanket neatly folded. A surge of emotions rushed through me as I touched the wool. All of the dreams, the many hours of hard work, and the financial sacrifices made by us over the years contained within the blanket. The genesis of Kagavi.

The blanket sits in the corner of our living room now. When I look at it, I see cardinal and gold pennants waving as the Ames eleven open a new season of hope. So many familiar faces—the striped jerseys bonding all in brotherhood. Fresh out of the time machine, ninety years new. So many stories contained in the fabric. I smell the river house and see Grandpa’s grin as the flickers of the campfire dance on his cheeks and his words hang in the air. The full-throated roar of the State Field crowd mixes with the river spray off the boat hull.